Punjabi’s unheralded role in the Great War

By Lookout on Nov 28, 2018 with Comments 0

Steve Purewal, Author Duty, Honour & Izzat ~

After 100 years, it is time to tell the tale of the unsung heroes of the Punjab who stood as brothers-in-arms with Canadians to make a critical contribution to Allied victories in the First World War.

This story of diverse communities coming together with a common goal to make the ultimate sacrifice is presented in my book Duty, Honour & Izzat, released to commemorate the centennial of the Armistice. It details the contributions of Punjabis that helped win the war.

War’s start

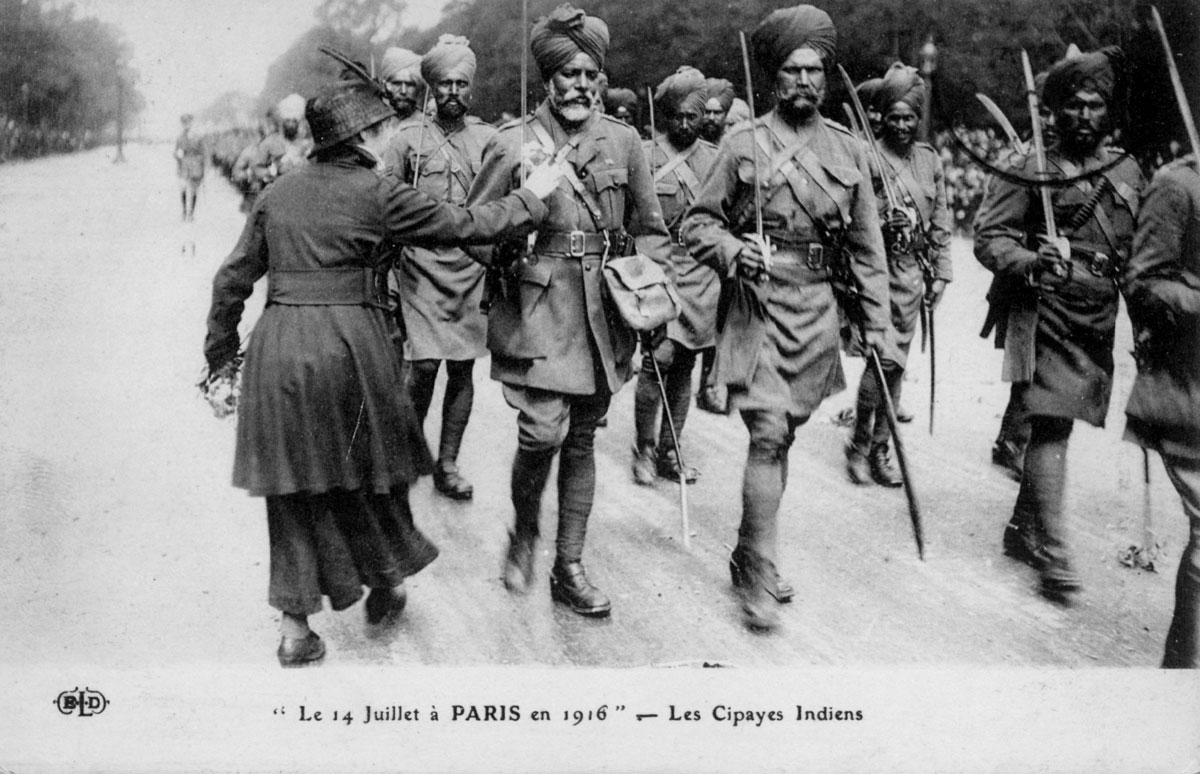

Arriving Sept. 26, 1914, in Marseille, France, British Punjab’s Lahore Division of pre-partition India became the first colonial force to deploy in Europe to defend liberty and freedom while millions of Europeans had yet to enlist.

With the fate of the Channel Ports hanging in the balance, the Indian Expeditionary Force quickly plugged the gap in the last British line of defence before Calais. They thwarted the German advance by forcing the opposing armies to complete a series of trenches in a stalemate that would stretch south from the Flanders coast to Switzerland.

After this First Battle of Ypres, the Western Front would remain more or less static for the next four years until August 1918 when the Canadians were able to punch a hole in the German line during the 100 Days offensive, which finally put the end of war within sight.

Speaking after the war, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces, Ferdinand Foch, identified the Indian Army as having delivered the war effort’s first decisive steps to victory; they were critical in stemming the tide of the German invasion of Belgium and France. Without their arrival in the nick of time, the port of Calais would not have been saved for a Canadian landing, the Western Front would have been breached, and the British Expeditionary Force annihilated. Without them, history may have indeed unfolded as strategized in Alfred von Schlieffen’s master plan with the taking of Paris in 42 days, and the war could well have been over by Christmas as many speculated at the time.

A what if moment

The Allied victory in November 1918 could have gone differently because of events in the waters off Vancouver in 1914, two weeks before war was declared in Europe.

For it was here, far from the fabled battlegrounds of Flanders, that the raising of HMCS Rainbow’s guns against British subjects aboard the Komagata Maru could have changed tides for the Empire.

In the summer of 1914, Punjabis, British subjects, many of whom were former soldiers, were denied entry to Canada and deemed undesirables. They were forced return to Calcutta (present day Kolkata), India. This was one of several incidents in the early 20th century in which exclusion laws in Canada were used to exclude immigrants of Asian origin.

People from this rejected community would eventually become 45 per cent infantry, 66 per cent cavalry and 85 per cent artillery of the only battle-tested colonial army available to the Crown when the war broke out.

More than a year later, some of these evictees would come to the side of Canadian soldiers to help hold the line at Ypres.

Second Battle of Ypres

It was April 22, 1915, when Germany resorted to chemical weapons to shatter Allied defences and standing directly in the path of their assault on Ypres were Canadian soldiers. After four days of brutal fighting allied reinforcements were dispatched – and as fate would have it those friends in need arriving to help hold the Canadian line were the Jalandhar and Ferozepur Brigades of the Lahore Division. These regiments hailed from the heartland of the Sikhs and comprised the exact same community aboard the Komagata Maru.

This Second Battle of Ypres marked a pivotal point in Canada’s nation-building myth, as it was arguably Canada’s most significant battle.

It set the Canadian Army’s tenor, style, and esprit de corps behind a fearsome reputation that would carry Canadian troops through the subsequent campaigns of the First World War on the road to Vimy.

Many of these battles would again feature Punjabi troops fighting alongside Canadians as at Festubert 1915, Somme 1916, Vimy 1917, Cambria 1917 and Passchendaele 1917.

All told, across the various theatres of war, India deployed as many men in the war effort as all the Crown’s white colonies put together.

Ultimately more than 74,000 South Asians were killed in the First World War; Indian casualties on the Western Front are buried or commemorated alongside Canadians in 115 cemeteries in France and Belgium.

Lest We Forget, 100 years on, we should honour all soldiers of the King that fought in The Great War for Civilization, and made the ultimate sacrifice for the freedoms and democracy we all enjoy today in Canada.

The all-volunteer Indian army upheld the Izzat (honour) of India on a global stage; they stood tall as friends in need at the darkest hour, winning more than 9,000 awards for gallantry (including 11 Victoria Crosses). This is a shared history between the mainstream and the Indo-Canadian minority. It is a dialogue around the ties that bind and the shared values of courage, integrity and selfless sacrifice. This is a common heritage that confronts the rise of divisive voices; it is a foundation for a shared future within a multicultural Canada.

About the Author: Steven Purewal is a community historian, curator and Managing Director of Indus Media Foundation, a registered non-profit society based in the lower mainland that seeks to foster an appreciation for Punjabi culture within the wider community. Steven has curated and produced the Duty, Honour & Izzat a WW1 Centennial commemoration exhibition that defines South Asian contributions to the Great War. Steven’s work has been featured at The National War Museum, Provincial museums, municipal venues and the Prime Minister’s Reception for the Komagata Maru Apology in Ottawa.

Filed Under: Top Stories

About the Author: