A tale of two heroes

By Lookout Production on Nov 14, 2022 with Comments 0

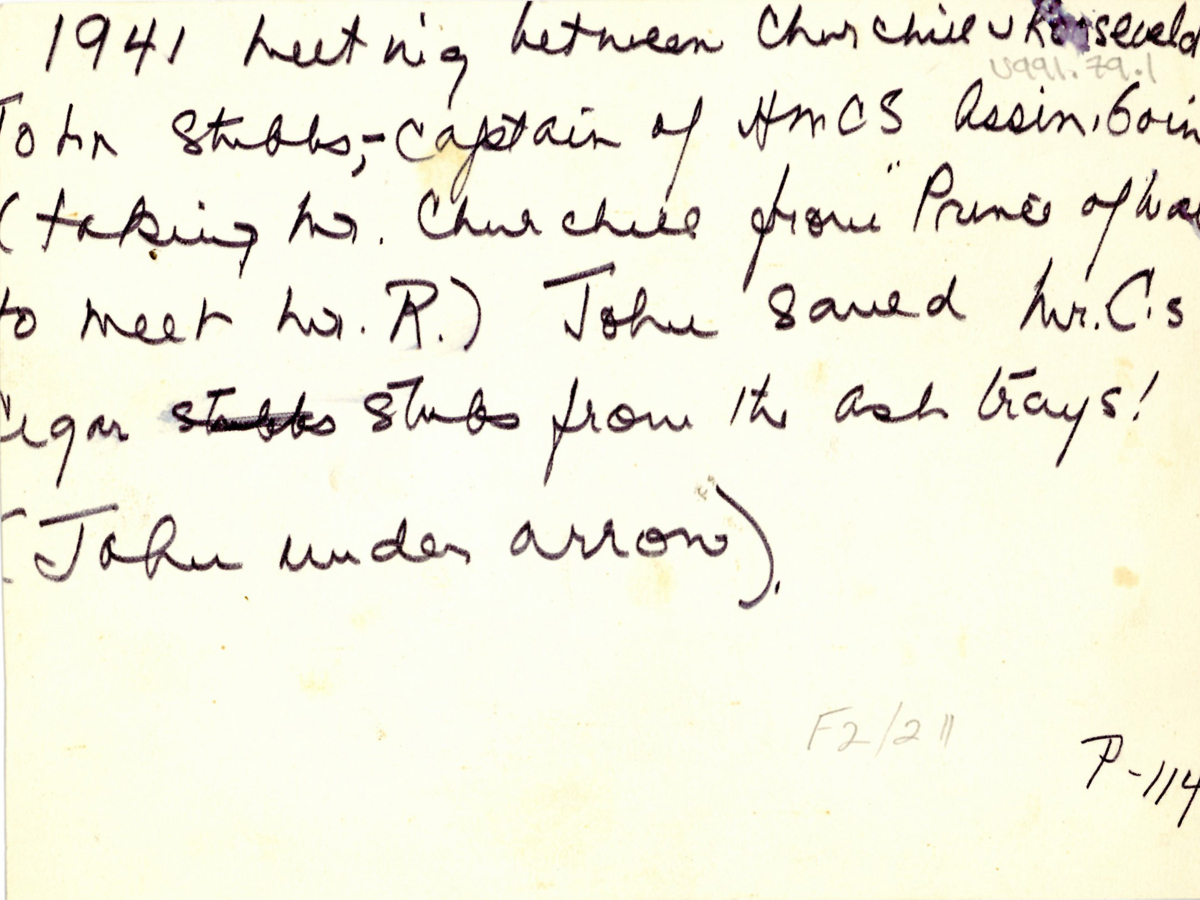

Prime Minister Churchill goes aboard Canadian destroyer – The historic occasion which marked the ocean meeting of the Right Honourable Winston Churchill and President Franklin D. Roosevelt was doubly significant for the officers and men of a Canadian destroyer who were hosts to the Prime Minister. Mr. Churchill is seen here boarding the vessel; on the extreme left of the photo, saluting in the foreground, is Lieutenant John H. Stubbs, RCN, of Kaslo, B.C., Commanding Officer of HMCS Assiniboine.

Clare Sharpe,

CFB Esquimalt Naval & Military Museum

—

The latest feature photo from the museum archives tells a tale of two heroes, two

leaders, two men who shaped history. Each played a key part in the Battle of the Atlantic, the epic seaborne struggle to defeat Nazism. Each was an inspiration to those who served with them, and to those they served.

The Right Honourable Winston Spencer Churchill and Lieutenant John Hamilton Stubbs of the Royal Canadian Navy met in the run-up to a decisive summit conference. Stubbs and the ship he commanded, HMCS Assiniboine, were detailed to escort Churchill, then-prime minister of Great Britain, to a secret meeting.

Assiniboine sailed with the Royal Navy vessel HMS Prince of Wales, which carried Churchill aboard, to Placentia Bay, Nfld. Stubbs and his men reportedly received little notice they would accompany Churchill to his now-famous first encounter with Franklin Delano Roosevelt, U.S. president. Their rendezvous took place at sea in early August 1941, just offshore from the little community of Ship Harbour, Nfld.

The British and American leaders joined together for secret talks – the U.S. was not yet in the Second World War, and negotiations were delicate. Their historic meeting resulted in a strategic set of agreements that gave birth to the Atlantic Charter and laid the groundwork for destruction of the Axis powers.

Shortly before their escort detail, Stubbs and Assiniboine had successfully sunk the submarine U-210, ramming the submarine twice and finishing it off with depth charges. Naval historian G. N. Tucker, who witnessed the action from the destroyer’s bridge, considered it a masterpiece of tactical skill on Stubbs’s part. Tucker observed that although Assiniboine’s bridge was deluged with machine gun bullets, Stubbs never took his eye off the U-boat, and gave his orders as though he were talking to a friend at a garden party.

Like Churchill, Stubbs was known for his strength under pressure and inspirational leadership. He left Assiniboine in October 1942 – now promoted to Lieutenant-Commander – to command his next ship, HMCS Athabaskan, a Tribal-class vessel with an unhappy reputation. Stubbs, who is described by historian Dr. Michael Whitby as a quiet, laid-back man with a strong sense of humour, quickly restored morale aboard Athabaskan, and ran an efficient yet relaxed ship.

Athabaskan was assigned to Plymouth Command to conduct offensive sweeps off the French coast. Stubbs’ skills proved well-suited to the fast-paced night surface actions, and he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his role in a battle in which Athabaskan and her sister-ship HMCS Haida played crucial roles in sinking the German destroyer T-29 on April 26, 1944.

Dr. Whitby recounts that three nights later, Athabaskan and Haida were on patrol in mid-Channel under Commander Harry DeWolf when they were ordered to intercept two German destroyers (survivors of the earlier battle) heading westward along the French coast.

“Athabaskan’s radar soon detected the enemy ships; minutes later, the Tribals opened fire, then altered course towards the enemy to ‘comb’ possible torpedoes (that is, turn parallel to incoming torpedoes). In spite of this maneuver, a torpedo found Athabaskan. The hit caused such devastation that Stubbs ordered the crew to stand by in readiness to abandon ship,” Dr. Whitby says.

In the early morning hours, as decks crowded with men, Athabaskan’s 4-inch magazine erupted in a massive blast. Most of those on the port side were killed, and many others were burned by searing oil that rained down on the upper deck. Survivors took to the cold waters of the English Channel as their ship began to sink beneath them, Dr Whitby recalls.

Stubbs is said to have sung to his men stanzas from a tune about naval volunteers called ‘The Wavy Navy’ while they waited in the freezing water. Badly burned and last seen clinging to a life-raft, John Stubbs was among the 128 who perished in the attack on Athabaskan. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) after his death.

The quiet heroism and dedication to duty demonstrated by John Stubbs have become a rightful part of the rich traditions of the Royal Canadian Navy.

To view the John Stubbs/Winston Churchill photo, and learn more about Canada’s military history, visit the CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum, open 7 days a week from 10 a.m.-3:30 p.m.

To learn more visit, www.navalandmilitarymuseum.org

Filed Under: Top Stories

About the Author: