Challenging Traditions: New museum exhibit focuses on women in the Navy

By Lookout Production on Apr 08, 2022 with Comments 0

Bernice “Bunny” McIntyre is seen distributing poppies in 2018 alongside her friend and fellow Somme Branch Legion member MWO (Retired) Paul O’ Boyle, RCN/CF.

Joanie Veitch

Trident Newspaper

—

The changing role of women in the Royal Canadian Navy took centre stage in a new exhibit that opened March 8 at the Naval Museum of Halifax.

While COVID restrictions still prevent members of the public from visiting the museum in person, museum director Jennifer Denty and exhibit co-curator CPO1 (Retired) JoAnn Cunningham, invited Capt(N) Sean Williams, CFB Halifax Base Commander, and CPO1 Alena Mondelli, Base Chief, to join them on a virtual tour that was also live streamed on the museum’s Facebook site.

“Traditionally, we would have had a large opening with speeches and finger food but given the COVID environment we’re still in, that just wasn’t feasible,” said Denty during a pre-show sneak peek.

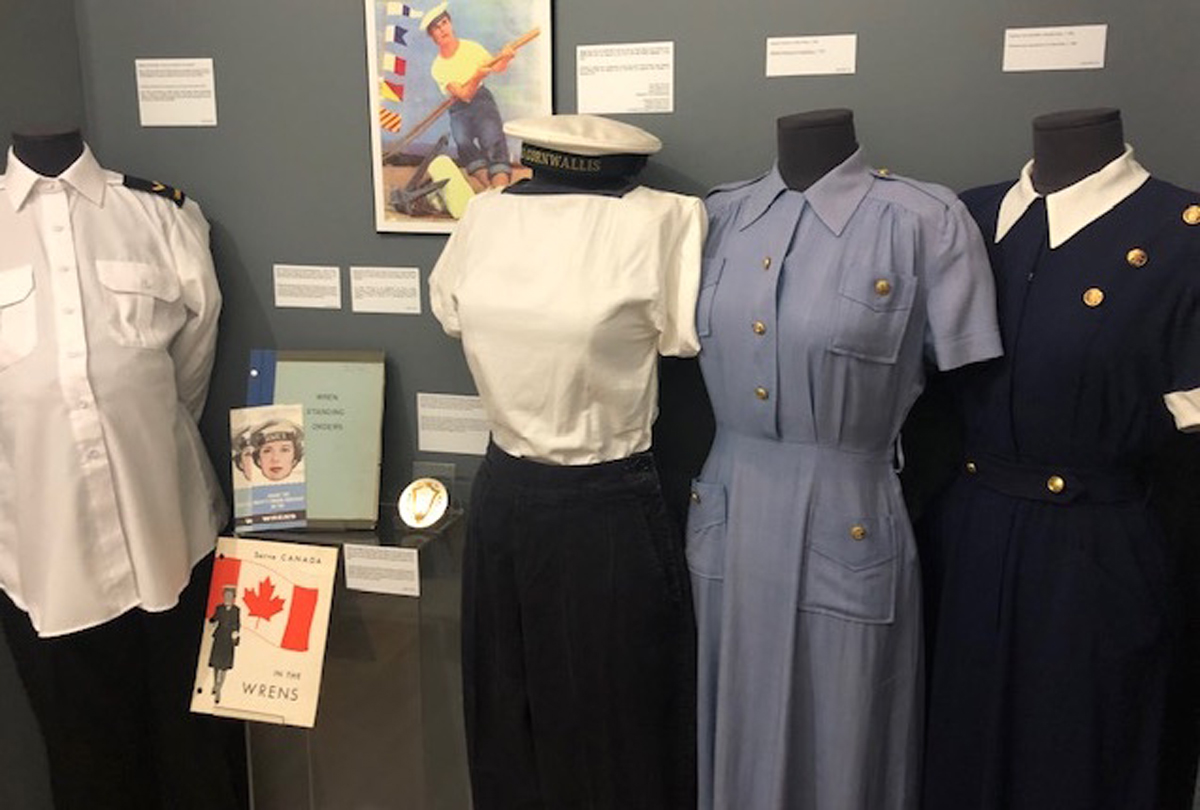

The new exhibit is housed on the lower level of the museum, in the former communications exhibit space. With large panels and artifacts from the early 1900s to present day, the display tells the story of women in the Royal Canadian Navy, highlighting their contributions and how the role of women in the navy has changed over the years.

“We’re quite pleased with how it turned out. It’s a story that needs to be told,” says Denty.

Nursing Sisters served with the Canadian military from the late 1800s through to the First World War, but women were not permitted to enlist in the navy until the Second World War, when on July 31, 1942, the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service (WRCNS) was established.

Following in the British tradition for the Women’s Royal Naval Service, the women in the WRCNS were known as Wrens, and several panels and displays in the exhibit tell their story.

At their peak during the war, more than 6,800 women served as Wrens in the RCN, with nearly 1,000 Wrens housed on the top two floors of a five-storey building, the Naval Engineering School, at HMCS Stadacona.

Trailblazing women are featured prominently throughout the exhibit, such as Adelaide Sinclair, who was appointed Director of the WRCNS in March 1943, and Isabel Macneill, a graduate of the first class of WRCNS who went on to become Commanding Officer of HMCS Conestoga. And Bernice “Bunny” McIntyre, who left her home in Dauphin, Manitoba, to join the WRCNS on Dec. 18, 1942.

“She said she joined the navy because she didn’t want to be stuck in Manitoba married to a farmer,” says CPO1 (Ret’d) Cunningham, who got to know McIntyre over the past number of years, up until McIntryre died last year, just a few months shy of her 100th birthday.

“She loved her time in the service but when she became pregnant with her first child in 1958, she was discharged from the military. At that time if you were pregnant you were considered medically unfit for service,” says CPO1 (Ret’d) Cunningham.

The rule disallowing women to continue service following pregnancy wasn’t changed until 1968 following a recommendation from the recently created Royal Commission on the Status of Women.

After the war ended, the WRCNS were demobilized on Aug. 31, 1946, and women were once again barred from military service until 1951, during the Korean War, when the navy again faced personnel shortages and enlisted Wrens to fill administrative and non-combatant roles.

Up until the late 1970s and early 1980s, women were largely relegated to support trades in the RCN, although the Naval Reserve continued to enrol a high percentage of women and readily integrated them into non-traditional trades and leadership roles.

While the items on display show the changing role of women from the war years through to present day, the exhibit also explores stereotypes and exclusionary policies, some that prohibited women from serving and others that continued to present challenges for decades, such as women not being allowed to join if married, or rules that barred women from serving on board ships.

Even when women were given more opportunities, not all women benefitted, says Denty. She notes that even after an early policy stipulating that “only men of European descent” could join the navy was dropped when the WRCNS was formed, only women of European descent were allowed to enlist.

“There was still a lot of discrimination for years after women began to enlist and there are certainly more stories to tell. This is only the beginning in telling those stories, but this is a very good start,” says Denty.

Filed Under: Top Stories

About the Author: