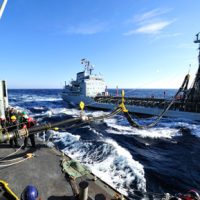

Ready to RAS-Charlottetown at sea

By Lookout on Apr 16, 2012 with Comments 0

The pipe was made, “Starboard watch, special sea-duty men, RAS teams three and five: close up for RAS with FGS Rhön! Dress: naval combat dress, negative ball caps.”

Personnel from all messes in HMCS Charlottetown began to take up their positions for a “liquid RAS” — replenishment at sea with fuel — with Rhön, the German refuelling ship accompanying Standing NATO Maritime Group 1.

Sailors put on their game face, for no one ever knows precisely what to expect: a calm, co-operative sea, or that stubborn windswept kind with spray tossing over the guardrails. Heavy weather can make a RAS more difficult than it already is.

In my opinion, replenishment at sea is one of the riskiest things we do in a Canadian warship, and we do it all the time. On this deployment, Charlottetown is patrolling as a part of NATO task force, so we are usually at sea for more than two weeks. To keep the fuel tanks topped up, the ship needs to RAS every three to four days.

To conduct a RAS, two ships with a combined mass equivalent to about 25,000 automobiles must maintain station about 50 metres apart for hours, often in difficult seas, while thousands of pounds of diesel fuel flows through 10-inch hoses suspended between them from heavy steel cables under tremendous tension.

The ships are never more than a few seconds from colliding, so a mechanical failure or the smallest mistake by the bridge team could be disastrous.

Nevertheless, with thoughtful preparations based on generations of experience, the crew of a Canadian warship minimizes the risk to the greatest extent possible before the refuelling ship is even in sight.

The bridge team isn’t the only group with an important job to do. On the RAS deck, where it all goes down, there are many hazards that everyone must be aware of.

We have to be particularly careful in the “dump” area, where the 10-inch hoses from the refuelling ship connect to the receiving ship. If either vessel lurches the wrong way, the cables that carry the hoses could snap in the blink of an eye and lash across the deck, tearing through everything (and everybody) in their path. Also, the guard rails have to be removed to accommodate the hoses, and this is where a fuel spill is most likely to happen. A careless move at the wrong time, and you could be over the side before you know it.

“A RAS certainly has the potential to be dangerous,” says PO2 Class Peter Strickland, Charlottetown’s Chief Quarter Master and the Petty Officer in charge of the RAS Deck. “It is critical that all personnel are trained and equipment is well maintained. Complacency or a mechanical failure could result in equipment damage, injury to personnel, or even loss of life. But with proper training, experience and confidence, it normally runs smoothly and without incident.”

As in every task Charlottetown undertakes, teamwork is the key to success in a RAS. It’s an all-ship evolution, which means the entire ship’s company works together as one. No matter what the circumstance may be, high winds or hard rains, Charlottetown is always ready to RAS.

LS Norman Snook, HMCS Charlottetown

Filed Under: Top Stories

About the Author: